70 million years ago, the surface of the Pacific split when its eponymous tectonic plate moved over a hot spot, thus producing a successive chain of islands over the northern stretch of the ocean.

Those islands ultimately became Hawaii—one of the remotest archipelagos on Earth and the recipient of more than 8.3 million visitors per year.

NEWS FLASH! Last night, November 27th 2022, Mauna Loa began erupting for the first time in 38.5 years! Last night’s glow could be seen from residents and visitors of Kona. An ashfall advisory is currently in place.

And while we tend to associate the 50th state with its six most populous islands—Oahu, Maui, the Big Island, Kauai, Molokai, and Lanai—the archipelago is in fact comprised of 132 islands, reefs, atolls, seamounts, and shoals, all of which span over 1,500 miles from the Big Island to the Kure Atoll—or Mokupapapa in Hawaiian.

What remains in the wake of that hot spot’s fiery action is a string of beauties crowned with riotous greenery, riven with dramatic waterfalls, lined with some of the world’s best beaches—and topped by the massive, captivating volcanoes that created them. Hawaiian Island geology is some of the most fascinating on Earth.

Here’s the lowdown on Hawaii’s top volcanos on its four most popular islands—and why you should consider visiting them:

The Big Island

Mauna Loa

Mauna Loa isn’t just historically considered the largest volcano on Earth—it’s also deemed the second-largest mountain in the entire solar system. While shorter than its neighbor Mauna Kea, what Mauna Loa may “lack” in terms of height it makes up for in its general vastness: Rising 13,679 feet above sea level, spanning a width of 75 miles, and covering a landmass of 2,035 square miles, it reinforces why the island of Hawaii earned the moniker big.

With a name that translates to “long mountain,” Mauna Loa could easily be considered Hawaii’s gentle giant, producing fluid, rather non-explosive eruptions, some of which serve as the foundation of present-day Hilo—the largest town on the island and home to one of the University of Hawaii’s locations. One of five subaerial volcanos that make up the Big Island—that is, “under the air” volcanoes that surge out of the sea—Mauna Loa shares an intricate, even knotty relationship with its neighboring volcanos (notably, that activity in one results in lower activity in the other; it also shares the same gravity well of Mauna Kea), so much so their proximity to each other has resulted in a series of earthquakes, as well as an offshoot of debris, known as the Hilina Slump, that is, in essence, evidence of Kilauea’s displacement. Formidable? Certainly—especially when you consider that Mauna Loa is also a survivor of the last Ice Age.

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: 13,679 feet above sea level

Age: 700,000-1 million-years-old

Last eruption: March 1984, but has just recently began erupting on November 27th, 2022!

Kilauea

As the most active volcano on the planet, Kilauea—whose name aptly translates to “spewing” or “much spreading”—has been perpetually erupting since 1983, rendering the Big Island’s Hawaii Volcanoes National Park one of the most dynamic and explosive—literally—tourist attractions in the islands. Having emerged on the southern edge of the island, Kilauea possesses two active rift zones, as well as an active fault that moves vertically year after year; roughly 90% of the volcano is encased with lava flows less than 1,100 years in age.

All of which may sound fascinating—but how does that translate for potential visitors? Consider this: “Kilauea is the only volcano on earth erupting from two different locations—from the summit crater and the Pu’u O’o vent in the remote East Rift Zone—at the same time right now,” Public Affairs specialist for Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Jessica Ferracane told Condé Nast Traveler. In 2017, the island, the magazine reports, “saw the amount of lava produced exceed recent records, and just a few months ago, a new lava ocean entry point was formed, called Kamokuna.” Approximately 100 feet above sea level, the entry point delivers more than one million gallons “of lava flow into the ocean every hour.” In turn, molten rock jets upwards and outwards, while plumes of steamy acid clouds rise steadily. This is the gritty and gorgeous creation of Earth at its finest—and an overt reminder that the only constant in life is change: Since 1983, Kilauea’s outpouring has created more than 500 new acres of land to the island of Hawaii, producing 200,000-500,000 cubic meters per day. And it’s done so without compunction: 187 structures have been destroyed by its flaming rock, including the Mauna Kea Congregational Church and the Royal Gardens Community Center. Still: Talk about spectacular.

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: 4,091 feet

Age: 300,000-600,000 years old

Last eruption: January 3, 1983-present

Mauna Kea

Towering nearly 14,000 feet above sea level, Mauna Kea isn’t just a sight to behold (and further evidence of Hawaii’s magnificence): Measured from its base on the seafloor, it greatly exceeds the height of Mount Everest, thus ranking it the tallest mountain on Earth.

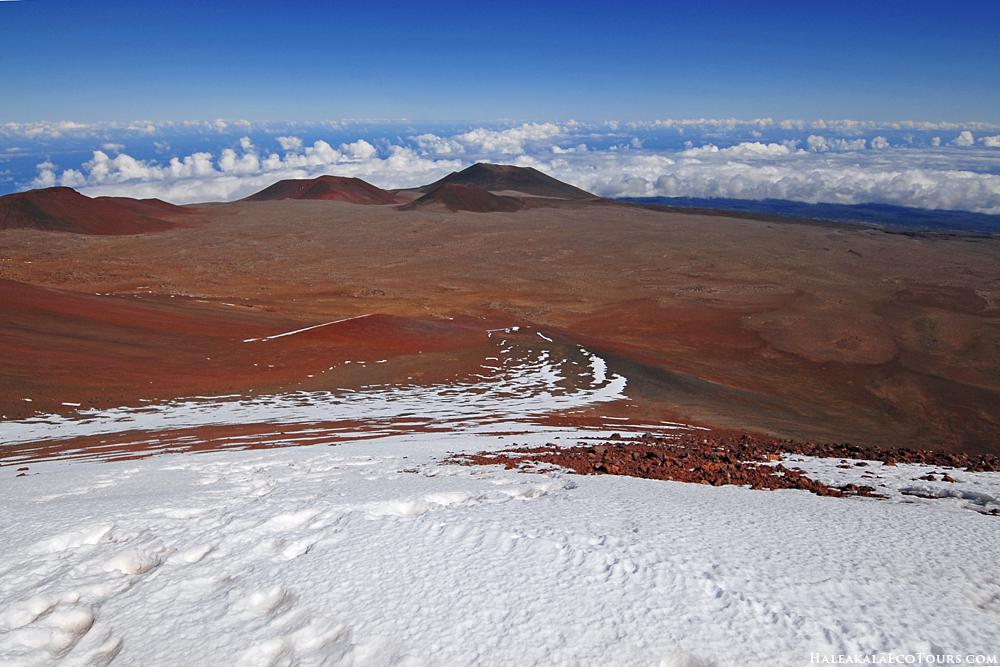

Ascending its slopes often goes down as one of the most memorable experiences one can have in the West. As one of the only spots in the world where you can rise 14,000 feet in two hours, the journey to its peak takes intrepid travelers through three diverse—and stunning—microclimates: a koa and ohia forest at its foot, a mamane-naio forest on its flanks, and an alpine climate at its apex—a zone so lofty it expands beyond the tree line, presents temps in the 30s, and lures blankets of snows to its lavascape (yes, snow in Hawaii!) And while the Aloha State may evoke images of sandy beaches and sunlit waters, Mauna Kea reigns in the realm of stars: With thirteen telescopes funded by eleven countries—to say nothing of its dry air and visual clarity—the “white mountain” (as its Hawaiian name translates to) and the highest peak in Hawaii is one of the most important astronomical research centers on the planet, housing the world’s largest observatory for infrared, optical, and submillimeter astronomy.

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: 13,803 feet

Age: Approximately 1 million-years-old

Last eruption: 2460 BC

Hualalai

Located on the western edge of the Big Island, Hualalai may not have erupted since 1801, but it’s nonetheless considered the third most active volcano of the five shield volcanoes that comprise the island of Hawaii. Expected to erupt in the next century, the rough-edged volcano—which goes down as the third youngest volcano on the island— boasts over 100 cinder and spatter cones around its three rift zones and makes up for approximately 7% of the Big Island, including the ground that underlies Kona International Airport.

The calmness the popular hiking destination has presented—scientists estimate Hualalai erupts every 200-300 years—has resulted in a boon for locals and the economy: Resorts, homes, and businesses have sprouted up on the volcano’s flanks, rendering it one of the leading regions in Hawaii for real estate. But, despite its glossiness, its allure is far from new: Ancient Hawaiians have been inhabiting Hualalai for centuries, with many of its villages dating back to before recorded history. Blame Mother Nature for what little remains of these original homesteads: Hualalai’s last eruption buried a number of Hawaiian settlements.

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: 8,271 feet

Age: Over 300,000 years old

Last eruption: 1801

Kohala

Shaped like a foot and boasting an ecosystem far different than its counterparts as a result of geographic isolation, Kohala is proof of the beauty of older things: Over a million years old—which renders the 5,480-foot mountain the oldest volcano on the Big Island—Kohala is fragmented by multiple deep gorges created by centuries of erosion, giving the volcano a texture (and greenness) distinct from its neighbors.

The erosion is believed to be responsible for its atypical shape. Though it breached the Pacific’s surface approximately 500,000 years ago, it had low volcanic activity—so low, in fact, that erosion corroded the volcano faster than it could rebuild itself, and resulted in part of the volcano weathering away into the ocean. Think of it as a fair trade: Its incredible age means that Kohala witnessed, and recorded, an about-face in magnetic polarity—a switch in the orientation of the Earth’s magnetic field (in which the North and South Poles interchanged) that occurred 780,000 years ago. The mountain, whose name translates to the “sound of white caps,” is also an impressive survivor: Seemingly displaced marine fossils suggest it endured a mammoth-sized tsunami 120,000 years ago.

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: 5,480 feet

Age: 700,000-1 million-years-old

Last eruption: 120,000 years ago

Loihi

Kama’aina frequently joke that Las Vegas is Hawaii’s ninth island. Well, move over, Sin City, as there’s another island in town: Loihi, which translates to “the long one,” is an active, underground volcano roughly 22 miles off the Big Island’s southeastern coast on the flank of Mauna Loa. The youngest volcano in the Hawaiian-Emperor seamount chain, Loihi presently stands as the only Hawaiian volcano in the deeply-submerged pre-shield phase of development—that is, an underwater stage chiefly characterized by low-volume eruptions of “pillow” lava (or, rounded balls of lava that are given scant time to cool before they confront water).

But before Hawaiian residents give up their annual trips to the Glitter Gulch, keep in mind that the formation of new land moves at the pace of a honu: It’s estimated that Loihi, which began taking shape 400,000 years, won’t start emerging from the sea for another 10 to 100,000 years. In the meantime, the infant landmass is proving to be a gift for geologists, in that it provides deeper insight to the formation of the entire Hawaiian Islands.

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: Approximately 10,000 feet above the ocean floor

Age: 400,00o years old

Last eruption: August 1996

Maui

Haleakala

Maui may have been created by two volcanos—Mount Kahalawai on the island’s western flank and Haleakala to the east—but it’s the latter of the two that is the Valley Isle’s star attraction.

There’s no why behind it: Scaling the sky at 10,023 feet, the gigantic shield volcano is the largest dormant volcano on Earth (keep in mind that the Big Island’s volcanos are either sleeping, active, or inactive). Its enormous depression is just as imposing as its elevation: the crater itself is seven and a half miles long and two and a half miles wide, rendering more than one to remark that its desolate space is large enough to fit the entirety of Manhattan Island (no small feat for a 727 square mile island in the center of the Pacific). The “House of the Sun” had its last eruption in 1790 sent a stream of lava to the southeast of the island, creating what we know today as La Perouse Bay, and while Jack London—he of The Call of the Wild fame—didn’t venture into Haleakala’s barren crater until 1907, he captured what remained perfectly when he wrote that Haleakala was “a workshop of nature still cluttered with the raw beginnings of world-making.”

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: 10,023 feet

Age: More than 1 million years old

Last eruption: 1790

Visit Haleakala on one of our luxury bus tours. (808) 575-9575

Oahu

Ko’olau

Tourists might flock to “The Gathering Place’s” sunny shores for the abundance of sleek resorts, superlative shopping, and terrific surfing it offers, but evidence of the volcano that created Hawaii’s busiest and most popular island is impossible to flout. Commonly known as Diamond Head, Leahi rests to the left of Waikiki and has, since Hawaii went mainstream, gone down as the most iconic image of the islands. Translated from Hawaiian as “the brow of the tuna,” Diamond Head—which was designated a National Natural Landmark in 1968—is a volcanic tuft cone that was created by the island’s Ko’olau Volcano, a 2.6-million-year old volcano that shears the sky and hovers above the state capital. Now frequently referred to as the Ko’olau Mountains, Ko’olau was once a single mountain whose western half was devastated in prehistoric times when the volcano’s eastern half fell into the ocean. Dormant, and standing at less than 3,200 feet, Ko’olau is dwarfed by its cousins on Maui and the Big Island, but this wasn’t always the case: Geologists believe that prior to the catastrophic landslide that collapsed its eastern flank, Ko’olau soared 9,800 feet above sea level. The impact may have demolished Oahu, but what remains is nothing short of astonishing: A range of opulent mountains that appear fluted from the island’s windward side.

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: 3,150 feet

Age: 1.7 million years old

Last eruption: 32,000-10,000 years BP (Before Present)

Kauai

Mount Wai‘ale‘ale

The antithesis of the dryness and desolation seen on the volcanoes of Maui and the Big Island, Kauai’s Mount Wai‘ale‘ale presents another story entirely: As the second-highest peak on Hawaii’s oldest and lushest island, this 5,148-foot majesty is famous for being the wettest spot in the world, with an average rainfall of 452 inches annually. From this has emerged a summit covered not in cinder cones and lava tubes but a verdant landscape teeming with tropical rainforests—including the Alaka’i Wilderness Preserve. (Otherwise known as the Alaka’i Swamp, this 9,000-acre expanse of boggy land houses some of Hawaii’s rarest plants.) With a name that means “rippling water” in Hawaiian, this radically-eroded volcano is the result of a volcanic eruption that once connected Kauai with its neighboring isle, Ni’ihau (now, the two distinct islands are separated by a channel that’s approximately 17.2 miles wide). And beyond its prodigious rain, it may be best known as the onlooker of Waimea Canyon—a 3,500-foot deep chasm that rightfully urged Mark Twain to dub it the Pacific’s Grand Canyon.

Quick glance at the stats:

Height: 5, 148 feet

Age: 4.2-5.6 million years old

Last eruption: 1.41-1.43 million years ago

Visiting Hawaii’s Volcanos

Beyond the Big Island, visiting the volcanos of Hawaii is, for the most part, readily accessible: Viewing the sunrise at Maui’s Haleakala Summit requires advance registration but it can otherwise be toured without a reservation; Oahu’s Ko’olau Mountains possess myriad hiking trails, and Kauai’s Mount Wai‘ale‘ale is best viewed by a four-wheeler.

Should you choose to see Hawaii’s volcanos in action, however, head to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park on the Big Island. Its visitor center is handsomely equipped with an array of information (including eruptive films), visual displays, and a bookstore; its staff is also available to answer questions. Within the park, you’ll also find the Jaggar Museum and Overlook, an exhibition hall that peers out at the Kilauea Caldera, where lava-lake sightings are a frequent occurrence. (The Jaggar Museum also boasts an excellent collection of Hawaiian legends.) Safety considerations and passes in hand (or a tour guide in your company), journey out into the sizzling wilderness where, aside from viewing Hawaii’s astounding volcanoes, you’ll find seven of the world’s 13 microclimates across its 505 miles, as well as the hauntingly-twisted shapes the collected volcanos have crafted. In other words, prepared to be staggered—after all, where else in the world can you see Earth literally being fashioned?

Some fun Volcanic Facts

- Magma is molten rock that is under the earth’s surface. When the pressure of the magma becomes too much, it breaks through the earth’s surface and erupts as lava.

- Lava is molten rock that flows from a volcano. It can be very hot, reaching temperatures of up to 1,000 degrees Celsius.

- Volcanic ash is made up of small pieces of rock and glass that are blasted into the air by a volcanic eruption. It can be very harmful to people and animals if breathed in. (let’s hope everyone is ok with this recent eruption on the Big Island.)

- Pyroclastic flows are fast-moving currents of hot gas and ash that can reach speeds of up to 700 kilometers per hour. They are extremely dangerous and can cause severe burns or death if caught in one.

- Volcanic bombs are pieces of lava that are blasted into the air during an eruption and then solidify before hitting the ground. They can be very large, weighing up to several tonnes.

- Lahars are mudflows that occur when water mixes with volcanic ash and debris. They can be extremely destructive, causing buildings and bridges to collapse.

- Volcanoes can cause tsunamis, which are large waves that can reach heights of over 30 meters. Tsunamis can cause extensive damage to coastal areas and even inland areas if they are large enough. These are usually the biggest volcanic threat to the Hawaiian Islands.

- Volcanic eruptions can cause climate change by releasing large amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. These gases trap heat in the atmosphere and cause the Earth’s temperature to rise

When I visited Hawaii, we took a helicopter tour in 2011 and we admired all the Islands, but there was one city built at the bottom of one volcano they say was dormant for many years, and I don’t remember the name. I would like to know if it’s still safe. feel so sad for the communities.